𝗞𝗲𝘆 𝗠𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗮𝗴𝗲

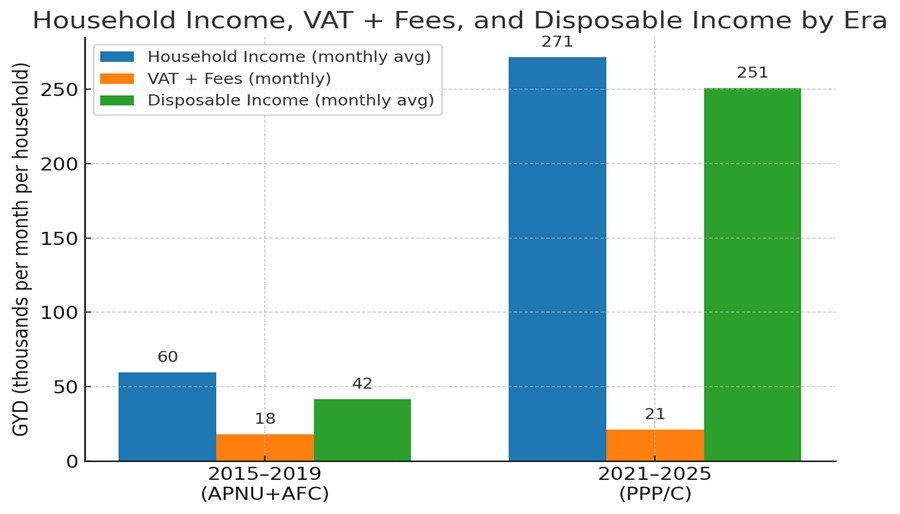

Between 2015 and 2019, households in Guyana saw nearly 30.1% of their household income consumed by VAT and fees under the APNU+AFC government’s policy of expanding VAT to over 200 goods and services. From 2021 to 2025, under the PPP/C government, the relative tax bite fell to just 9.34% of household income, even as total VAT collections remained high. As a result, average monthly disposable income per household jumped from GYD 41,632 to GYD 250,591—a sixfold increase.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗕𝗮𝗰𝗸𝗱𝗿𝗼𝗽: 𝗧𝘄𝗼 𝗣𝗼𝗹𝗶𝗰𝘆 𝗘𝗿𝗮𝘀, 𝗧𝘄𝗼 𝗩𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗗𝗶𝗳𝗳𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗢𝘂𝘁𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗲𝘀

𝟮𝟬𝟭𝟱–𝟮𝟬𝟭𝟵: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗔𝗣𝗡𝗨+𝗔𝗙𝗖 𝗩𝗔𝗧 𝗘𝘅𝗽𝗮𝗻𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻

The APNU+AFC government expanded VAT coverage to more than 200 previously exempt goods and services. Average monthly household income was about GYD 59,618, while VAT and fees averaged GYD 17,933 per month—representing roughly 30.1% of income. This left households with an average disposable income of GYD 41,632 per month, limiting growth in consumption and investment at the household level. At roughly GYD 60,000 per month in 2015–2019, a typical family saw around GYD 18,000 go to VAT and other fees—before rent, utilities, or groceries.

2021–2025: The PPP/C Reversal and Income Surge

Under the PPP/C, VAT on many goods and services was rolled back, lowering the relative tax burden sharply. Average monthly household income surged to GYD 271,425, with VAT and fees averaging just GYD 21,183 per month—only 9.34% of income. This allowed disposable income to soar to GYD 250,591 per month, enabling households to spend, save, and invest at levels not seen in the previous era.

𝗙𝗶𝗴𝘂𝗿𝗲 𝟭. 𝗚𝗿𝗼𝘄𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗶𝗻𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗲𝘀, 𝘀𝗵𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗮𝘅 𝗯𝗶𝘁𝗲 — 𝗛𝗼𝘂𝘀𝗲𝗵𝗼𝗹𝗱 𝗜𝗻𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗲, 𝗩𝗔𝗧 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗢𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗙𝗲𝗲𝘀, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗗𝗶𝘀𝗽𝗼𝘀𝗮𝗯𝗹𝗲 𝗜𝗻𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗲 𝗯𝘆 𝗘𝗿𝗮 (𝗽𝗲𝗿 𝗵𝗼𝘂𝘀𝗲𝗵𝗼𝗹𝗱, 𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗵𝗹𝘆, 𝗲𝗾𝘂𝗮𝗹 𝟱-𝘆𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝘁𝗲𝗿𝗺𝘀). VAT and other fees fell as a share of household income under PPP/C, leaving families with far more to spend and invest.

𝑪𝒐𝒏𝒄𝒍𝒖𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏

Tax policy is not just about percentages—it’s about what families keep. The APNU+AFC years show that expanding the tax base without matching income growth erodes disposable income. The PPP/C years demonstrate that a lighter tax bite, paired with strong income growth from wages, welfare, and subsidies, can deliver robust tax revenues and far higher take‑home pay. For households, that difference is tangible: more money left after taxes—month after month. One government took a bigger slice of a smaller pie; the other grew the pie and took a smaller slice.

𝗠𝗲𝘁𝗵𝗼𝗱𝗼𝗹𝗼𝗴𝘆 & 𝗗𝗮𝘁𝗮 𝗦𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗲

This analysis uses total national household income (in GYD millions) and the number of households (in thousands) to derive per-household income. VAT and fees per household are taken from national budget estimates. Relative tax burden is calculated as VAT + fees divided by total household income. All figures are converted to per-household monthly values for comparability. Era averages are based on full terms only: 2015–2019 (APNU+AFC) and 2021–2025 (PPP/C). Transition years are excluded to ensure a fair comparison between complete administrations. Data for 2015–2024 are actual figures based on budget estimates, while 2025 figures are projections based on the Budget 2025 estimates. The wages component of household income only captures wages within the income tax bracket; it does not include wages under the income tax threshold or informal income. Sources: Budget Estimates 2015–2024; Budget 2025 (projected).

𝗡𝗼𝘁𝗲𝘀

Calculation notes: Burden % = (VAT and other fees per household ÷ annual income per household). Example (PPP/C average): 21,183 × 12 ÷ 271,425 × 12 ≈ 9.34%.