The Chinese business community has, over decades, established a strong global footprint across Africa, South America, and the Caribbean, including Guyana. Their entrepreneurial drive and willingness to invest are not, in themselves, negative. On the contrary, foreign investment is essential for economic growth. However, investment must be accompanied by responsibility—economic, social, and cultural.

In Guyana today, there is a visible and widening disconnect between many foreign-owned retail and hardware businesses and the local population. While these businesses operate extensively within our economy, there is little evidence of meaningful cultural participation, community engagement, or integration with Guyanese society. These businesses operate in isolation, not in partnership.

Guyana is a multicultural nation built on the shared histories and traditions of Indo-Guyanese, Afro-Guyanese, Amerindian, and mixed communities. Successful commerce here has always depended on understanding people, culture, and trust. When businesses operate solely as shopkeepers—without engaging with local traditions, respecting social norms, or building relationships—they create distance rather than value.

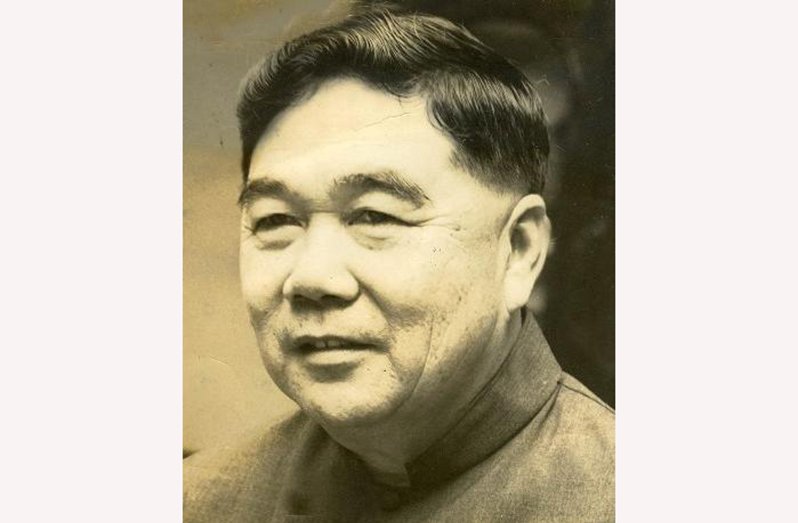

History shows a different model. Earlier generations of Chinese migrants to Guyana integrated deeply into society. Many married locally, participated in community life, and became Guyanese in every sense of the word. They contributed not only to commerce but also to nation-building. The first President of Guyana, Mr Arthur Raymond Chung, was the first ethnic Chinese head of state of a non-Asian country.

This detachment between the new Chinese shopkeepers and the local community becomes especially troublesome when combined with serious economic concerns. Legitimate, tax-compliant Guyanese corporate businesses are reporting billions of losses, particularly in the hardware and retail sectors. January sales alone have fallen sharply, even as operational expenses continue to rise. At the same time, government revenues are falling.

There are allegedly growing allegations of anti-competitive practices, misuse of duty-free concessions, and goods imported under special project exemptions entering the general retail market. A visit to large outlets such as Freshgo raises questions about how containers are allegedly cleared and what classification they are placed under. If duty-free imports intended for mining or infrastructure projects are diverted to retail, the state loses substantial VAT and customs revenue.

Equally concerning are alleged reports of cross-border trade with Brazil conducted through Guyana. The process reportedly involves importing goods using Guyana dollars, converting them to US dollars, selling them across the border, and extracting foreign currency or gold, resulting in a direct loss of Guyana’s foreign exchange. If true, this represents not only revenue leakage but also a threat to national financial stability.

These are not cultural issues; they are governance issues. They require urgent attention from regulators, customs authorities, and economic policymakers.

There is also the matter of representation. The Private Sector Commission (PSC) has historically avoided accepting ethnic organisations, focusing instead on business entities. By its nature, the Chinese Association functions more as a cultural body than a commercial one. This raises legitimate questions about precedent, governance, and international perception. For example, the United States maintains AMCHAM separately from broader private-sector groupings. These distinctions matter.

Taxation, fair competition, and regulatory compliance must be the basis for engagement—not ethnicity or political expediency. Businesses should not seek shelter behind cultural associations when questions of duty, VAT, and market fairness arise.

This is not an attack on any community. It is a call for accountability, integration, and respect for the country that provides the opportunity to do business. Guyana welcomes investors—but not at the expense of its people, its revenues, or its social cohesion.

Conclusion: Guyana First, Fairness Always

Guyana’s economy must work for Guyanese. Foreign businesses operating here must pay their full share of taxes, comply with competition laws, and engage meaningfully with the society from which they profit. Cultural understanding is not optional—it is integral to doing business in a diverse nation.

Investment without integration breeds resentment. Commerce without compliance weakens the state. Guyana does not need isolationist shopkeepers; it needs development partners. The responsibility now lies with regulators, business councils, and policymakers to ensure that growth is inclusive, fair, and firmly rooted in the national interest.