Summarypoints

Suriname’sfiscalregimemaybeabetterdeal[onpaper]incomparisontoGuyana’sStabroek Block’s fiscal regime. But, in actuality, Guyana enjoys a better deal for the following reasons:

- Deliberate Government policies and stewardship of the sector, chiefly; the Government’s accommodative policy to ramp up production levels as quickly as possible, to reach 1.5 millionbpd by 2028-2030.

- The Suriname government’s profit oil split is calculated in accordance with the R-Factor formula, which ranges from as low as 20% profit oil to as high as 80% profit oil. Nonetheless, these higher profitability outcomes in favour of Suriname are highly unlikely. Accordingly, the maximum profit split Suriname is guaranteed is more likely to range between the 20%-25% R-Factor rates.

- Suriname has a participation right of up to20% if it elects to exercise same, according to thefiscal terms. But profit oil will not be realized until after the investment cost has been fully recovered. This means that during the cost recovery period, the Government’s Take willconstitute the 36% corporate tax and 6.25% royalty only.

- Guyana has a lower break-even-cost per barrel: In Suriname, it is estimated that the break-even cost could be as high as US$45 per barrel or as low as $US$35 per barrel, averaging US$40 per barrel. Conversely, Guyana’s break-even cost ranges between US$27–US$35 per barrel.

- Guyana also has a lower debt-to-equity ratio of 49% in contrast to Suriname’s 74%.Consequently, the financing cost for Guyana accounts for 3.5% of revenue, in contrast to Suriname’s 9.14%. Effectively, with the higher debt financing and the higher cost associated with the debt financing in relation to revenue; in Suriname, the taxable income would be significantly reduced by these amounts, thereby accruing alower overall profit oil and corporate income taxfor Suriname as opposed to Guyana.

- By2028-30,Guyanawillbeproducingapproximately1.5millionbpdincontrasttoSuriname’s

0.220 million bpd. Further, by that time, in actuality, the Guyana Government’s Take will be 3.2x more than Suriname in the cost recovery period, and 7.4x more than Suriname in the post- recovery period, all things being equal.

Introduction

After a commercial discovery of crude oil offshore Suriname was announced in 2020, four years later (Oct 01, 2024), TotalEnergies announced Final Investment Decision(FID) for the GranMorgu development on Block 58. The project includes a 220,000 barrels of oil per day Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) unit, that replicates a proven and efficient design. Total investment is estimated at around US$10.5 billion, and first oil is expected in 2028.

TotalEnergies is the operator of Block 58 with a 50% interest, alongside APA Corporation (50%).Staatsolie hasannounceditsintentto exercise itsoptionto enterthe development project with up to 20% interest. The Partners agreed that Staatsolie will contribute to the project from FID and will finalize its interest before June 2025.

It was subsequently reported in the local media, in Guyana, that Staatsolie’ s head boasted about their more favorable fiscal terms for Suriname, when compared to Guyana’s Stabroek Block fiscal terms.

However, although it is true that Suriname’s fiscal regime, which constitutes 6.25% royalty, 36% income tax and a 20% profit split in accordance with the “R-Factor”formula, may be a better deal [on paper] than Guyana’s Stabroek Block’s fiscal regime, which constitutes 2% royalty and a 50% profit share; it is worthwhile to perform adeeper, pragmatic comparative analysis in order to truly ascertain which of the two countries will actually be earning more dollars into their national coffers.

In the case of Guyana, the Stabroek Block Petroleum Agreement (PA) of 2016 was negotiated by the former, APNU+AFC Government, which was heavily criticized, and commonly described as a “lopsided deal”. And by the time the current Government assumed office following the 2020 general and regional elections, which they won, ExxonMobil and their Co-venture partners (the Contractor) had already moved into production under the 2016 PA. This, in turn, made it difficult to renegotiate given the “Stability Clause” in the Agreement and the Contractor’s unwillingness to renegotiate.

Notwithstanding, the PPP/C Government was determined and committed towards maximizing the in-country value from the 2016 PA, without renegotiating. This was achieved, vis-à-vis, deliberate Government policies and stewardship of the sector, such as: the enactment of the Local Content Act (2021), the Gas-to-Energy (GtE)project (by 2025), and the Government’s policy to ramp up production levels as quickly as possible. To this end, production commenced at 120,000 barrels per day (Bpd) in December 2019, which increased to over 640,000 bpd in 2024, and is poised toincrease to over 1.5 million bpd by 2028-2030.

Discussionand Analysis

BriefHistoryofSuriname’sOilIndustry

Staatsolie is Suriname’s national oil company (NOC), established in December 1980 to execute that country’s oil policy. The policy stipulates that foreign oil companies canonly explore for and eventually produce oil through Service Contracts with Staatsolie. Staatsolie is also involved in oil exploration and production independently. In 1965, commercial oil was first discovered onshore in Suriname, and commercial oilproduction (onshore) began in November, 1982 at 200 barrels per day.

In 2020, commercial oil was discovered for the first time offshore Suriname, and first oil is expected to commence in 2028, according to TotalEnergies announced development plans.

Suriname’sFiscalRegime

Suriname’s fiscal regime for the petroleum industry is administered through aProduction Sharing Contract (PSC), between the Contractors (foreign oil companies) and Staatsolie (on behalf of the Suriname Government). Suriname’s fiscal terms can be summarized as follows, pursuant to the PSC:

- Costoilrecoveryceilingof80%afterroyalty

- Unrecovered cost oil balances are carried forward until fully recovered on a project-by-project basis. This means that each project is not ring-fenced, which is a notion propagated in Guyana. Rather, each commercial fields are ring-fenced, bearing in mind that a singular commercial field can have multiple projects developed in phases.

- Staatsoliehasparticipationrightsofupto20%atdevelopmentplan

- Suriname’s corporate tax rate of 36% and Net Operating Losses (NOLs) carried

- Taxable income = (Cost Oil + Profit Oil + Other Income if any)–(Opex + Exploration/Appraisal Capex + Depreciation of Development Capital + non- recoverable costs).

- ProfitoilissubjecttothefollowingR-Factor calculation:

Formula:

(Cum. Revenue. – Cum. Royalty. – Cum. Tax); where: CumulativeCosts

Explanationofthe“R-Factor”Formula

The Suriname government’s profit oil split is calculated in accordance with the R-Factor formula,whichrangesfromaslowas20%profitoiltoashighas80%profitoil.TheR- Factoressentiallyguaranteesthe

foreignoilcompaniesorcontractorsahigherprofit split when oil prices are lower, and with higher oil prices, the government is guaranteed a higher profit split, capped at a maximum of 80%. However, it is highly unlikely that Surinamewillbeabletocashinonthemaximumguaranteedprofitsplitof80%―after studying the historical trend in oil price movements―coupled with the long-term forecastsforoilprices.Ofnote,thisisafteraccountingforthepotentialimpactofthe global energy transition agenda and climate change policies.

To illustrate how the R-Factor calculation is applied, various outcomes were tested inthe financial model using a variety of prices. To this end, at current price, which is around US$80, the R-Factor is 1.5, which guarantees a 25% profit share. To achievethe 30% profit split, oil prices would have to surpass US$100-US$120 boe; to achieve the 40%-50% profit split, oil prices will have to surpass US$150/boe, and to achieve the 80% profit split, oil prices will have to surpass US$200/boe. Nonetheless, these higher profitability outcomes in favour of Suriname are highly unlikely. Therefore, the maximum profit split Suriname is guaranteed is more likely to range between the 20%-25% R- Factor rates.

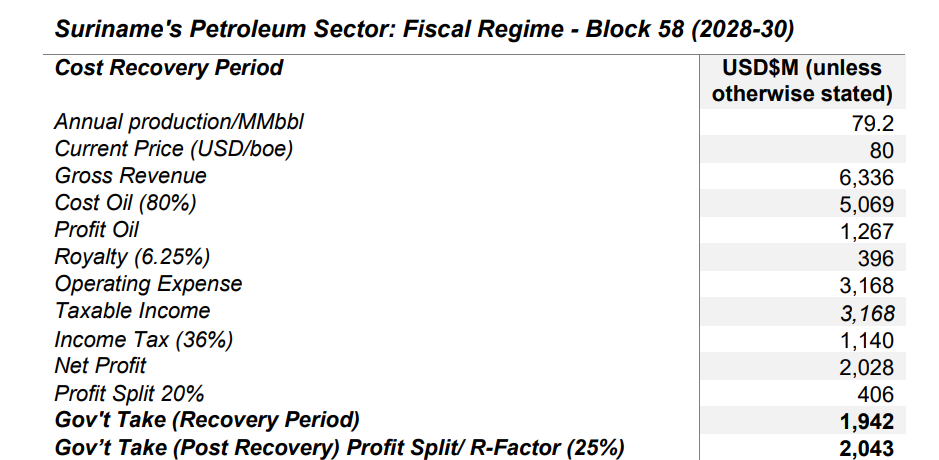

Table(i):ScenarioAnalysis,Suriname

Table (i)hereunderpresentsascenarioanalysisof Suriname’sBlock58 considering the stated project economics for the GranMorgu development, after applying the fiscalterms pursuant to the PSA, at current brent crude oil price.

Resultantly, the analysis shows that by2028 (first oil), the Suriname Government will be earning US$1.9 billion during the cost recovery period, representing an effective tax of 30.7%, which will increase marginally to US$2 billion annually in the post recovery period annually, representing an effective taxrate of 32.3%, reflecting an increase in the effective tax rate by 1.6 percentage points.

It should be noted that, while Suriname has a participation right of up to 20% if it elects to exercise same, according to the fiscal terms, profit oil will not be realized until afterthe investment cost has been fully recovered. This means that during the cost recovery period, the Government’s Take will constitute the 36% corporate tax and 6.25% royalty only.

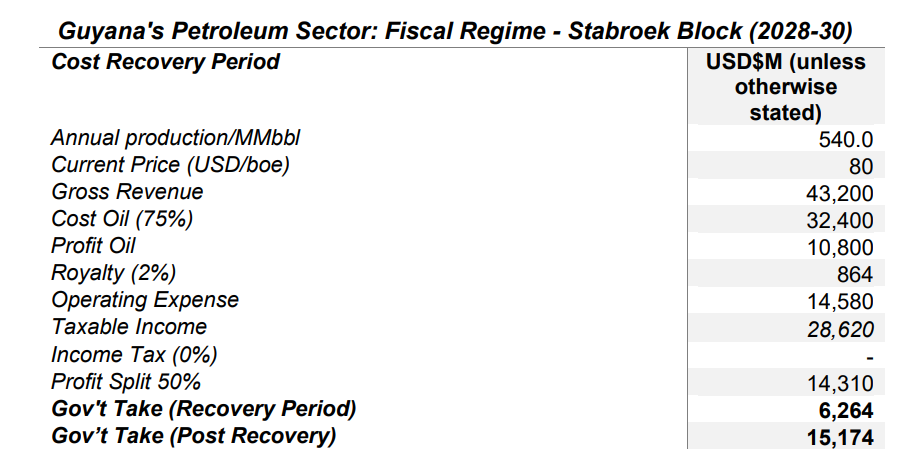

Table(ii):ScenarioAnalysis,Guyana

In the case of Guyana, particularly the Stabroek Block, which is governed by the 2016 Petroleum Agreement, by 2028-30, Guyana is on track to producing an estimated 1.5 million bpd.

Thus, with a 2% royalty and 50% profit share at current brent crude oil price, theGuyana Government’s Take during the cost recovery period is an estimated US$6.3 billion annually, representing an effective tax rate of 14.5%, and US$15.2 billion annually in the post recovery period, representing an increased effective tax rate of 35.1%, an increase by 20.6 percentage points.

Another contributing factor to this outcome is the difference in the break-even cost per barrel in Suriname versus Guyana. In Suriname, it is estimated that the break-even cost could be as high as US$45 per barrel or as low as$US$35 per barrel, averaging US$40 per barrel. Conversely, Guyana has a lower break-even cost ranging between US$27– US$35 per barrel.

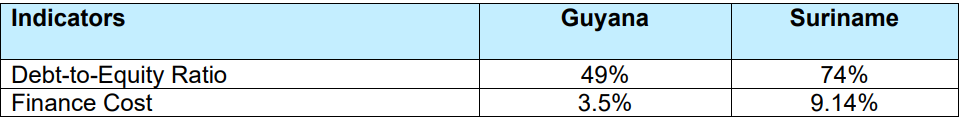

Table(iii):CapitalStructureandFinanceCost:GuyanaVs.Suriname

Thefinancecostforthedebt financingemployed inthecapitalstructure typicallyhastax implications that would ultimately affect the Government’s Take in both profit oil and corporate income tax. In this respect, the finance cost for the debt financing isaccounted for as an expense in the income statement, which, in turn, reduces the taxable income.

As shown in table (iii) above, Guyana has a lower debt-to-equity ratio of 49% in contrast to Suriname’s 74%. As such, the financing cost for Guyana accounts for 3.5% of revenue, in contrast toSuriname’s9.14%. Effectively, with the higher debt financing and higher cost of capital in relation to revenue for Suriname, the taxable income would be significantly reduced by these amounts, hence, accruing a lower overall profit oil and corporate income tax for Suriname as opposed to Guyana.

Conclusion

Altogether, the analysis conducted herein demonstrates that Suriname has a very different fiscal regime for their petroleum industry, which is more complex when compared to Guyana.

With that being established, it is important that when examining these two countries comparatively―that the present realities―and status of development in the industry be considered―aimed at presenting a fair, practical and realistic perspective.

Guyana’s remarkable success is attributed to the Government’s accommodative and intentional policies together with its stewardship of the sector. The national objective, in this regard, is geared towards maximizing the value derived from the sector, without renegotiating the terms of the 2016 Agreement, given the stability clause―and more so, averting the implications thereof.

Suriname on the other hand, has not been unable to replicate Guyana’s success, wherein Suriname will be moving to first oil production eight years after commercial discovery, and whereas Guyana was able to move to first oil production in four years after commercial discovery.

Moreover, by 2028-30, Guyana will be producing approximately 1.5 million bpd in contrast to Suriname’s 0.220 million bpd. Further, by that time, in actuality, the Guyana Government’sTakewillbe3.2xmorethanSurinameinthecostrecoveryperiod,and

7.4xmorethan Surinameinthepost-recoveryperiod,allthingsbeingequal.

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Democracyguyana, an online newspaper.